Freemasonry

Freemasons, known popularly for their white aprons, arcane symbols and secret handshake, are members of the world’s oldest fraternal organization. Despite its longevity, Freemasonry (sometimes known simply by the shortened Masons) has long been shrouded in mystery. To outside observers, the organization’s rites and practices may seem cult-like, clannish and secretive — even sinister.

Some of this stems from Freemasons’ often deliberate reluctance to speak about the organization’s rituals to outsiders, according to Time(opens in new tab). But it is also partly the result of many popular movies and books, such as Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code(opens in new tab)” (Doubleday, 2003), that have fostered misconceptions or depicted the order in an unflattering light.

In reality, however, Freemasonry is a worldwide organization with a long and complex history. Its members have included politicians, engineers, scientists, writers, inventors and philosophers. Many of these members have played prominent roles in world events, such as revolutions, wars and intellectual movements.

In addition to being the world’s oldest fraternal organization, Freemasonry is also the world’s largest such organization, boasting an estimated worldwide membership of some 6 million people, according to a report by the BBC(opens in new tab). As the name implies, a fraternal organization is one that’s composed almost solely of men who gather together for mutual benefit, frequently for professional or business reasons. However, nowadays women can be Freemasons, too (more on this later).

But Freemasons, or Masons as they are sometimes called, are dedicated to loftier goals as well. Bound together by secret rites of initiation and ritual, its members ostensibly promote the “brotherhood of man,” and in the past, have often been associated with 18th century Enlightenment principles such as anti-monarchism, republicanism, meritocracy and constitutional government, said Margaret Jacob(opens in new tab), professor emeritus of European history at the University of California, Los Angeles(opens in new tab) and author of the book “The Origins of Freemasonry: Facts and Fictions(opens in new tab)” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

This is not to say that Freemasonry is wholly secular and devoid of religious aspects. Its members are encouraged to believe in a supreme being, which in the parlance of Masonry, is known as the “Grand Architect of the Universe,” Jacob added.

Related: Why does Christianity have so many denominations?

This Grand Architect, is comparable to a Deistic creator rather than a personal God as envisioned by Christianity, according to Jacob. The concept of Deism, which has its origins in the 17th century Enlightenment, promotes the idea that the supreme being is like the ultimate “watchmaker;” a deity that created the universe but does not play an active role in the lives of its creations.

A code of ethics also guides the behavior of members. This code is derived from several documents, the most famous of which is a series of documents known as the “Old Charges” or “Constitutions.” One of these documents, known as the “Regius Poem” or the “Halliwell Manuscript,” is dated to sometime around the latter 14th or early 15th century, and is reportedly the oldest document to mention Masonry, according to the Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry(opens in new tab), an online magazine written by Freemasons. The Halliwell Manuscript is written in verse, and in addition to purportedly tracing the history of Masonry, it also prescribes correct moral behavior for Masons. For example, it urges members to be “steadfast, trusty, and true,” and “not to take bribes” or “harbor thieves.”

While many Freemasons are Christians, Freemasonry and Christianity have had a complex, often divisive, relationship. Some orthodox Christians have taken issue with Freemasonry’s Deism and its frequently perceived ties to paganism and the occult, according to Pauline Chakmakjian(opens in new tab).

But the Catholic Church has been among its harshest critics. In 1738, a Papal decree prohibited Catholics from becoming Freemasons, Jacob wrote. Even today, the Papal ban on Freemasonry remains in place, with the Church declaring Freemasonry “irreconcilable with the doctrine of the Church,” according to the Vatican(opens in new tab).

The origins of Freemasonry are obscure, and the subject is rife with myth and speculation. One of the more fanciful claims is that the Freemasons are descended from the builders of Solomon’s Temple (also known as the First Temple) in Jerusalem, according to Jacob. Others have argued that the Freemasons began as an offshoot of the Knights Templars, a Catholic military order dating to medieval times, according to Sky History(opens in new tab).

The famous American revolutionary Thomas Paine attempted to trace the origins of the order to the ancient Egyptians and Celtic Druids. There has also been a longstanding rumor that Freemasons are the same as the Illuminati, an 18th-century secret society that began in Germany, Jacob wrote. Most of these theories have been debunked, though some people continue to believe them.

“Freemasonry has its origins in the stonemason guilds of medieval Europe,” Jacob told Live Science. These guilds, especially active during the 14th century, were responsible for constructing some of the finest architecture in Europe, such as the ornate Gothic cathedrals of Notre Dame in Paris and Westminster Abbey in London.

Like many artisan craft guilds of that time, its members jealously guarded their secrets and were selective about who they chose as apprentices. Initiation for new members required a long period of training, during which they learned the craft and were often taught advanced mathematics and architecture. Their skills were in such high demand that experienced Freemasons were frequently sought out by monarchs or high-ranking church officials, Jacob said.

The guilds provided members not only with wage protection and quality control over the work performed but also important social connections, she added. Members gathered in lodges, which served as the headquarters and focal points where the Masons socialized, partook in meals and gathered to discuss the events and issues of the day.

However, with the rise of capitalism and the market economy during the 16th and 17th centuries, the old guild system broke down, Jacob wrote. But the Masonic lodges survived. In order to bolster membership and raise funds, the stonemason guilds began to recruit non-masons. At first, the new recruits were often relatives of existing members, but they increasingly included wealthy individuals and men of high social status.

Many of these new members were “learned gentlemen” who were interested in the philosophical and intellectual trends that were transforming the European intellectual landscape at the time, such as rationalism, the scientific method and Newtonian physics. The men were equally interested in questions of morality — especially how to build moral character. Out of this new focus grew “speculative Freemasonry,” which began in the 17th century. This modernized form of Masonry deemphasized stone working and the lodges became meeting places for men dedicated to and associated with liberal Western values, Jacob said.

“Freemasonry as we know it today grew out of the early 18th century in England and Scotland,” she said. A major turning point in Freemason history occurred in 1717, when the members of four separate London lodges gathered together to form what became known as the Premier Grand Lodge of England. This Grand Lodge became the focal point of British Masonry and helped to spread and popularize the organization. Freemasonry spread rapidly across the continent; soon there were Masonic lodges scattered throughout Europe, from Spain and Portugal in the west to Russia in the east. It was also established in the North American colonies during the first half of the 18th century, according to Jessica Harland-Jacobs.

By the late 18th century, at the height of the Enlightenment, Freemasonry carried considerable social cachet. “Being a Mason signaled that you were at the forefront of knowledge,” Jacob said.

Freemasonry wasn’t always welcomed, however. In the United States in the 1830s, for example, a political party known as the Anti-Masonic Party formed, the Washington Post reported(opens in new tab). It was the nation’s original third political party and its members were dedicated to countering what they believed was Freemasonry’s undue political influence. William Seward, who went on to become President Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, began his political career as an Anti-Masonic candidate.

The early Masonic lodges were exclusively male, meaning that women were prohibited from membership, a point made clear in the “Old Charges” (“no bondmen, no women, no immoral or scandalous men…”). This tradition, a principle that reflected the predominant social arrangements of the time, continued for many decades, especially in Great Britain.

But over the years, women increasingly began to play active roles in the organization, especially on the European mainland. In France during the 1740s, for example, so-called “lodges of adoption” began to appear, Jacob said. These were lodges that admitted a mixture of men and women, the latter mostly the wives, daughters and female relatives of the male Masons. They were not fully independent but were sanctioned by and attached to the traditional male lodges. Soon, similar lodges of adoption sprang up in the Netherlands and eventually in the United States.

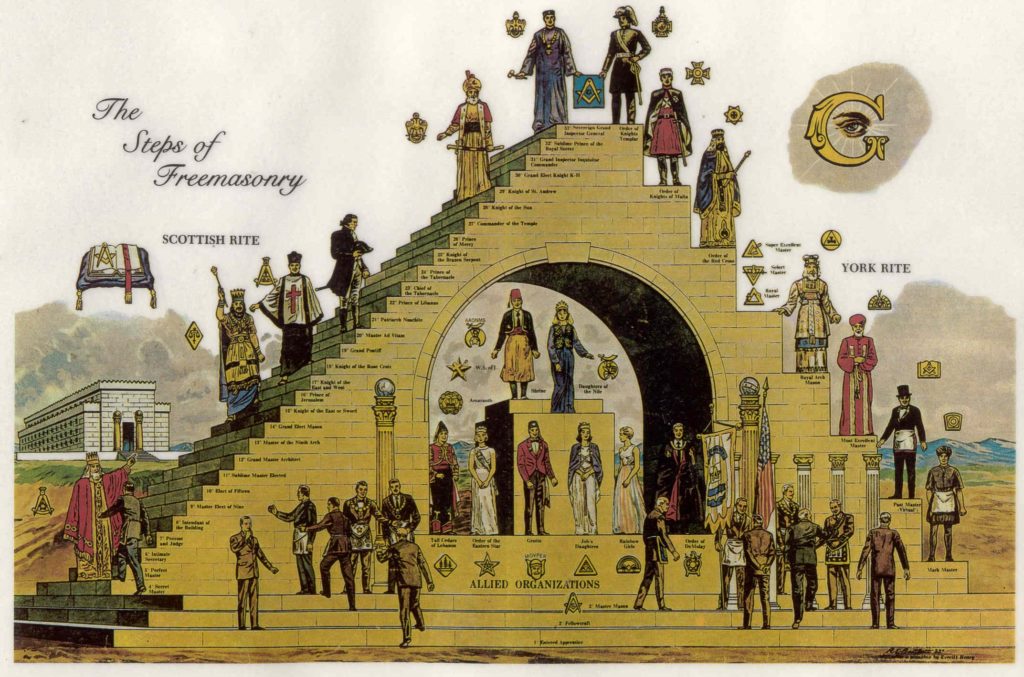

Out of this tradition, Masonic organizations were eventually formed that admitted both men and women as full members. Some of these organizations included the Order of the Amaranth, the Order of the White Shrine of Jerusalem and the Order of the Eastern Star(opens in new tab). In these organizations, both men and women partake in Masonic rites and women can hold positions of authority and leadership.

The highest ranking woman in the Order of the Eastern Star, for example, is known as the “Worthy Matron” and is the presiding officer of the organization. There are also several Masonic-related girls’ and young women’s organizations, such as the Order of Job’s Daughters and the International Order of Rainbow for Girls, both of which are active today. The Rainbow Girls are an offshoot of the Order of the Eastern Star and is largely dedicated to service and charity, according to Masonry Today(opens in new tab).

A California native, who asked to remain anonymous, and who was a member of the Rainbow Girls in the 1970s, remembers the organization fondly. As a young woman, she said, she was never made to feel lesser because she was a member of one of the female organizations. “We were autonomous,” she told Live Science. “We always decided our own agenda. If anything, looking back, the organization gave me a glimpse of a slightly utopian society because we were very democratic. The organization was well run and well organized.”

Today, traditional Masons are still exclusively men but the related organizations of female Masons are still active, many involved in charity, education and character-building.

Similar to its relationship with women, Freemasonry in the United States has had a complicated history with ethnic minorities, especially Black Americans. After Freemasonry was established in the American colonies, but prior to the Revolutionary War, a few free Black colonists, including a man named Prince Hall, petitioned for membership in the Boston, Massachusetts Lodge, according to Cécile Révauger’s book “Black Freemasonry(opens in new tab),” (Simon and Schuster, 2016).

Hall was denied but he persevered, eventually receiving a charter in 1784 from the Grand Lodge in England. The Masonic lodge he established was the first African American lodge in the United States, and became the basis for the many other Black lodges that subsequently sprang up. These Black lodges were named “Prince Hall Lodges” in the founder’s honor, and were established exclusively for African Americans.

Although the Masonic codes do not strictly prohibit the membership of non-white ethnic minorities, integrating the mainstream lodges has been an on-going struggle. Attempts to integrate the mainstream lodges have been met with varying success. “There are liberal lodges that make the extra effort, but most just go with whoever turns up,” Jacob said.

However, even as late as the first decade of this century, attempts to integrate some lodges in the southeastern United States have met with opposition from some white members, the New York Times reported.

Several prominent historical figures have reportedly been Freemasons, including Simón Bolívar, known as the “liberator of South America”, according to Business Insider(opens in new tab); the French philosopher Voltaire, known for his voluminous philosophical and political writings; and the famous German poet and writer Goethe, according to Freemasonry Matters(opens in new tab). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the famous composer, became a Mason in 1784. His renowned opera, “The Magic Flute,” contains elements of Freemasonry, and is a paean to his Masonic beliefs, NPR reported(opens in new tab).

In his book “Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730-1840(opens in new tab)” (University of North Carolina Press, 1998), historian Steven Bullock noted that several of the Founding Fathers and notable American revolutionaries and presidents were Freemasons, including George Washington, Paul Revere, Benjamin Franklin and Andrew Jackson. Franklin was one of the first Freemasons in what was then Colonial America, and in 1734 he became the Grand Master of the Philadelphia Lodge, according to a 1906 article published in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography(opens in new tab).

THE SYMBOLS OF FREEMASONRY

The world of Freemasonry is composed of esoteric signs and symbols that are baffling to most non-Masons. Perhaps the most common are the compass and square, which are the universally recognizable symbols of the organization. They typically emblazon the lintels above lodge entrances and can be found on the aprons worn by Masons during rituals.

Although there is not a single, universally agreed upon meaning, most Masons would probably contend that these two objects in conjunction are meant to represent how a Mason should conduct himself, according to an online dictionary of Masonic symbols(opens in new tab). The square signifies that a man should act “square” with his fellow man — that is, he should be honest and forthright in all his dealings. The compass is a reminder to engage in moderation, and not to get carried away by life’s vices.

In general, Masonic symbols — such as the beehive, the acacia tree and the all-seeing eye, to name a few — are meant to invoke ideals, remind members of correct modes of conduct and behavior, and impart important lessons.

“The symbols of freemasonry largely have to do with ethics — how one should live their life,” said the former-Rainbow Girl.

Related: Cracking codices: 10 of the most mysterious ancient manuscripts(opens in new tab)

IS FREEMASONRY STILL RELEVANT?

Today, Freemasonry is undergoing a decline, according to a 2020 article by.

“The lodges are having a terrible time recruiting men,” Jacob said. “Most young men today don’t accept these kinds of distinctions — such as places exclusively for men and places exclusively for women.”

Consequently, membership in lodges has dropped and the pull to join an exclusive, privileged enclave of men does not carry the attraction it once had. Although there are Masonic lodges in every U.S. state, many of these now stand vacant.

One of the reasons for this decline has been competition from similar fraternal and service organizations, such as the Odd Fellows, the Knights of Columbus, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks and E Clampus Vitus. But it’s also possible that this decline can be explained by the different values espoused by the newer generations, value systems that are often at odds with the previous generations.

The problem of decline, Jacob said, is rooted in the current composition of the lodges. Most members, she noted, are between the ages of 50 and 60, are predominantly white and hold very conservative politics. “This has no appeal to the younger generation,” she said. “Even the armed services are integrated now by race and gender, but not the lodges.”

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Watch this short, animated video about what Freemasons actually do, from The Infographics Show on YouTube(opens in new tab). Learn more about Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” and how it represents his initiation into Freemasonry in this video from the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra(opens in new tab). Read how Smithsonian Magazine(opens in new tab) described a tour of Washington D.C.’s Masonic Temple in 2007.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Dan Brown “The Da Vinci Code(opens in new tab)” (Doubleday, 2003)

- Hamish Mackay, “Freemasons explain the rituals and benefits of membership”, BBC News, 28th February 2018

- Margaret C Jacob, “The Origins of Freemasonry: Facts and Fictions(opens in new tab)” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005)

- “The Religious Poem: Halliwell Manuscript” Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry

- Declaration on Masonic Associations, The Vatican

- Cécile Révauger’s book “Black Freemasonry(opens in new tab)” (Simon and Schuster, 2016)

- Shaila Dewan and Robbie Brown, “Black Member Tests Message of Masons in Georgia Lodges”, The New York Times, 2nd July 2099

- “Mozart Meets the Masons: The Magic Flute”, NPR, October 23rd 2009

- Steven Bullock “Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730-1840(opens in new tab)” (University of North Carolina Press, 1998)

- Julius F. Sachse, “The Masonic Chronology of Benjamin Franklin” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 30, No. 2 (1906)

- Robert Mitchell, “How an abduction by the mysterious Freemasons led to a third political party, the nation’s first”, The Washington Post, October 21st, 2018

- Jessica Harland-Jacobs “Freemasonry and Colonialism”, The Handbook of Freemasonry (Brill, 2014)